We finally did it.

We joined the rest of the world in seeing Hamilton the Musical, riding its transcendent emotion last night at the Denver Performing Arts Center.

As Lin Manuel Miranda writes into the score, Hamilton penned 51 of the 85 treatises comprising the Federalist Papers, which I’ve been reading since high school.

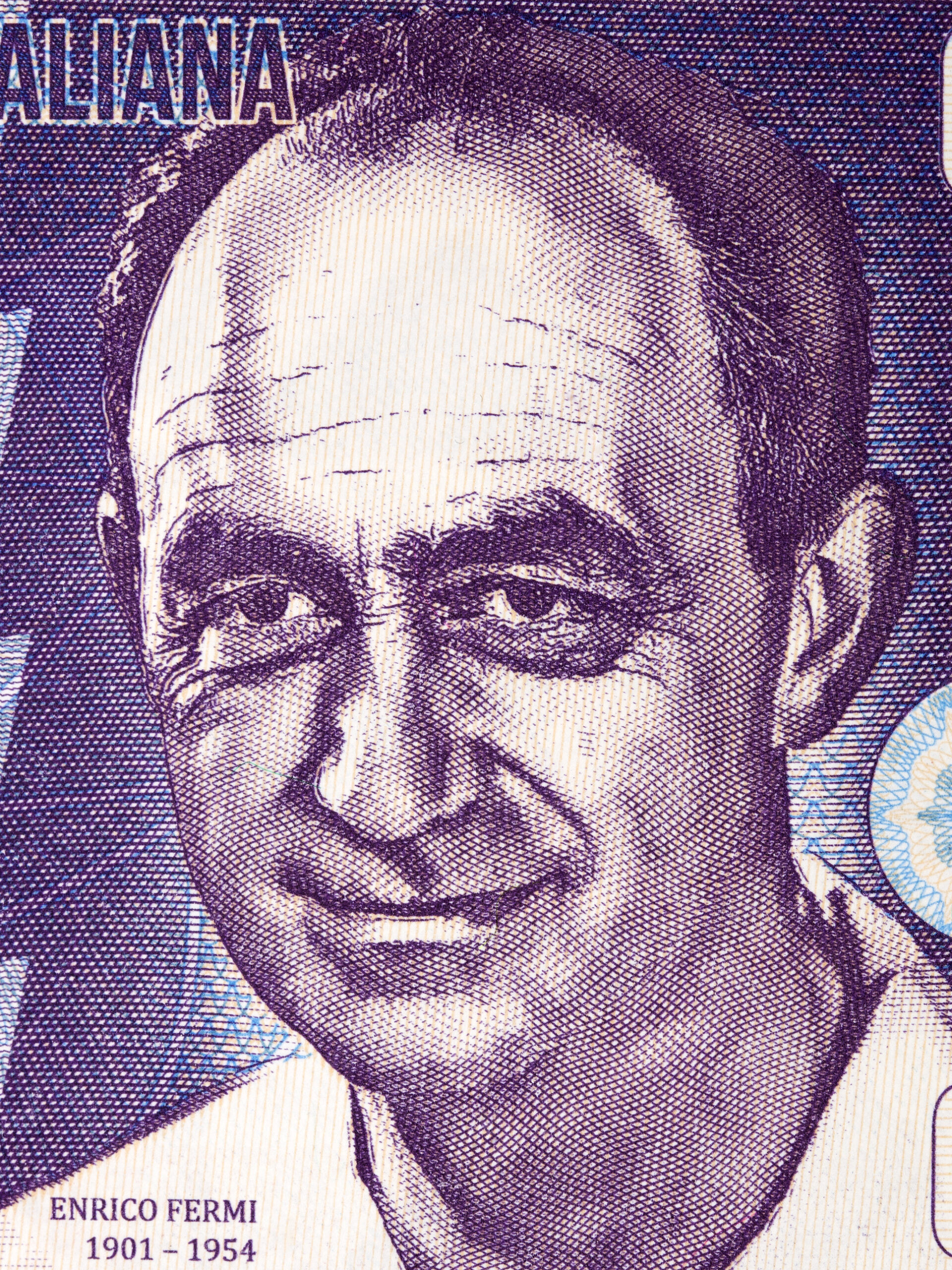

And he persuaded President Washington and the first Congress to create a national bank, giving the world confidence the young nation would not default on its war debts.

Since the re-election of Donald Trump, I’ve seen a half-dozen animated discussions on TV about ending the Federal Reserve, the distant stepchild of Hamilton’s bank.

It’s amusing because my dad talked about Ron Paul, who wrote a book called, “End the Fed” (which I’ve read). My wife Karen grew up with the Paul family in Lake Jackson, TX. We visited Rand Paul some years ago in his Washington DC office.

But talk of ending the US central bank elicits chortles from the powerful, sneers, knowing looks like, “Yeah. That’s crazy talk.”

We’re led to believe the Federal Reserve is vital to employment in the USA and the fiscal stability of the country. You hear Fed chair Jay Powell talk about policies advancing “our dual mandate” of stable prices and maximum employment.

I’ve long said in email exchanges with people at the WSJ, CNBC, that the Federal Reserve Act has no dual mandate. The Act says that the Fed is to maintain moderate interest rates so as to promote maximum employment – whatever that is – and stable prices. If anything, the mandate is moderate rates.

Amid soaring 1970s post-gold-standard inflation, the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act signed in 1978 by President Carter (the original inflation-reduction act) aimed at 3% or lower inflation so long as getting to the target didn’t cause unemployment. The Act called for zero inflation by 1988.

We instead had 10% unemployment as then Fed Chair Paul Volcker battled inflation by hiking interest rates to 20%. At the time, the Fed wasn’t printing money, so lifting rates prompted hoarding of cash in interest-bearing accounts. Fewer dollars chased goods. Inflation receded.

Alan Greenspan, Fed chair from 1987-2006 (long tenure!) aimed for inflation of zero percent because the definition of stable prices is no inflation.

Now the Fed has a 2% inflation target – unstable prices – and a dual mandate. And inflation post-Pandemic zoomed above 9%. For much of the past twenty years, interest rates were near zero percent, which is not moderate at all.

One concludes that the acts of Congress are suggestions to the Fed that it may interpret in ways that upon reflection appear to be the opposite of congressional language.

Yet it’s heresy to say we don’t need the Federal Reserve.

Just one time in the history of the country have we had no debt: Under Andrew Jackson in 1835.

President Jackson didn’t renew the charter for the second Bank of the United States, instead liquidating it, producing an $18 million surplus for the country – more than the entire budget then.

The Treasury paid off interest-bearing notes and distributed the surplus to the states. Woo hoo! Debt free!

Debts returned to the USA with the Mexican War and the Civil War. But there was no central bank for 80 years, and the USA became the world’s largest economy.

And there was no inflation in the 19th century. In fact, a basket of goods compiled by the Minneapolis Federal Reserve equivalent to today’s consumer price index declined in price by 50% from 1800-1900. Purchasing power!

Inflation is a modern phenomenon, not a historical one. Thousands of years of human history and experience with banking was but for brief periods devoid of inflation.

The national debt was $29 million in 1857 and surged to $3 billion by 1869 from funding the Civil War. It fell quickly back to $2 billion by 1871 and was still $2 billion in 1907 despite massive national growth.

Then a new central bank formed in 1913: The Federal Reserve. By July 1919, the national debt was $27 billion from funding WWI.

The rest is history. We’ve had inflation ever since and today the national debt is $36 trillion. We’ve not lived within our national means in a century.

The Fed is not alone responsible for our pervasive, debt-funded culture, propagated round the planet now, thanks to the ubiquity of greenbacks.

But we should learn from history, a la Hamilton. A central bank that can issue currency to buy government debt and government-guaranteed mortgages is going to promote growth through debt and inflation. And sooner or later, a catastrophic currency collapse.

The Constitution’s principal purpose as envisaged by Hamilton, Madison, Jefferson, was to serve as a bulwark against the predilections of human nature to abuse power.

Nothing should be sacrosanct. Recognizing that human nature has beset American finances, leading to staggering debt, requires a hard look in the national mirror. If Andrew Jackson did it, someone else can.

I’m not saying ending the Fed is the best solution. But I doubt Alexander Hamilton would sing the modern bank’s praises.